Ancient Religion as Science: An Introduction to Fetal Mythology

How does our primordial journey in utero relate to the origins of religion?

A Brief History of Prenatal and Perinatal Psychology

Does mental life start in the womb, at birth, or after? Historically, this question is age-old; inquiries span across cultures and epochs. Western thought held the Aristotelian belief that the soul and mind began developing at "quickening," the moment a fetus first moved in the womb—a concept now understood as the initial fetal movements, which modern science associates with the development of neural and motor pathways sometime in the second trimester. This general idea carried itself through the centuries, echoed by Thomas Aquinas, and incorporated into the British legal system until recently.

Although not cited directly by Aristotle when it comes to the forming of the soul, Ancient Greek civilization owes much of its foundational knowledge to the Ancient Egyptians, for whom prenatal life was of central importance. It was built into their official ceremonies, where the placenta of the pharaoh was wrapped in a bundle and treated with reverence during royal processions.

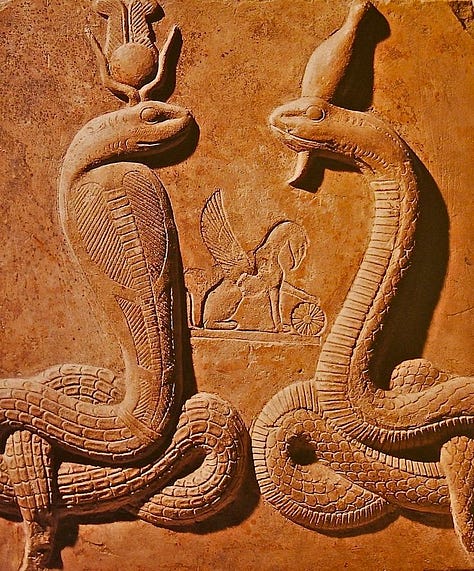

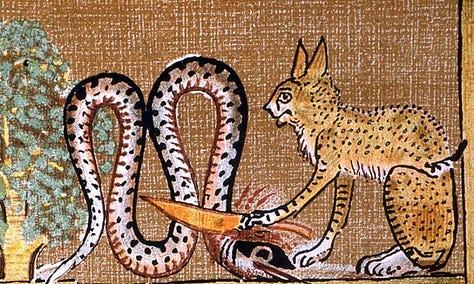

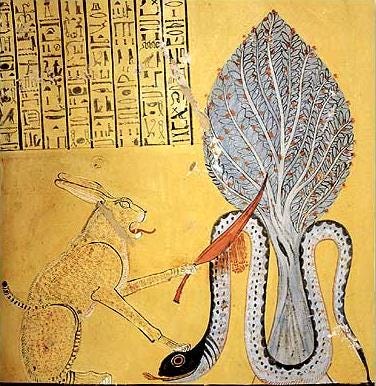

All over the world, traditions exist for the care of the embryo and the developing fetus, suggesting the existence of a mind in utero. Creation mythology with images of eggs, wombs, bags (representing the amniotic sac, as in the North American creation myth “A Bag Hung in Space”), serpents (the umbilical cord—see Hopi myth, the caduceus symbol, etc.), and young heroes signifying the fetal journey to birth or ancestral rebirth.

The theme of the fetal mind also exists in Asia. According to Chinese and Japanese tradition, the newborn is a year old at birth. In Indonesia and India, customs involving care for the embryonic soul reflect our own natural tendencies to mind the emotional state and environmental quality of the mother for the sake of the developing fetus. The practice of “navel-gazing,” according to Indian psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar is a “contemplation of that which separates the individual’s consciousness from its universal roots,” i.e. the mysterious and powerful placenta. Various rituals involving the particular storage or burial of the placenta around the world would be considered primitive by modern standards, but are remnants of reverence for this cosmic connection in the womb.

It wasn’t until humanity emerged from the tumult of the Industrial Revolution that we see the question of the beginning of mental life revitalized through the prism of psychoanalysis. Sigmund Freud, the dominant mind in this new specialized discipline, was adamantly opposed to the idea of a mind before birth—the implications of which could threaten his early childhood developmental theories that were growing in prominence. When his constituent Otto Rank suggested it in his 1924 book The Trauma of Birth, he was ousted from the psychoanalytic school by Freud, leading to his marginalization and suppressing interest in prenatal psychology for decades.

Western society has progressed significantly from the days when birthing women were sedated with ether and chloroform. However, it is worth noting that until the 1980s, infants were not given anesthesia for surgical procedures due to the belief that they lacked a developed nervous system capable of feeling pain or forming memories.

Ten years after Freud’s death and a quarter century after Rank’s work went out of print, the field was revived, still under relative obscurity, by Nandor Fodor in his 1949 book The Search for the Beloved: A Clinical Investigation of the Trauma of Birth and Prenatal Condition. Fodor expanded on Rank’s insights, exploring the psychological imprints of the prenatal period and its influence on personality, however, both agreed that “the physical environment within the womb is perfect,” demonstrating a fundamental disconnect from obstetric realities. We’ve evolved from this era thanks to advancements in neuroscience and ultrasound technology—but the question of unconscious psychological imprints made in the prenatal stage is still relatively unexplored in the modern zeitgeist.

Since Fodor, only a handful of psychologists, mostly psychoanalysts, have explored this area. Stanislov Grof conducted regression research among patients with LSD, positing the significance of the birth experience based on his patients’ tendency to relive it in therapy. Lloyd deMause founded an offshoot discipline called “psychohistory” in which he applied the intricacies of the “fetal drama” to wider societal and cultural phenomena, arguing with empirical evidence that humans collectively mimic the prenatal experience in expressions of group fantasies, whether they be innovative, depressed, manic, or violent. Others—albeit few—have dedicated their careers to fetal psychology and produced works of interest. However, the single psychologist who cited the ancient world for more than surface-level evidence with a disclaimer of superstition, was Francis Mott, a disciple of Nandor Fodor.

Francis Mott and the Science of Myth

In exploring mythological and religious texts to inform his obstetric and psychological research, Mott was keenly aware that advancement does not necessarily occur on a line. Knowledge, expressed metaphorically in myth, encompasses insights into natural processes and human experience. These include understanding life cycles, cosmic patterns, and the interconnectedness of existence, aspects of reality that earlier cultures intuited but are often overlooked today. Prenatal and perinatal researchers contemporaneous with Mott may refer to the existence of birth imagery in mythology, but only to illustrate its longevity or fundamentality as a subject of interest. Jungians (followers of the psychoanalytic theories of Carl Jung), for example, would claim that mythological birth imagery comes from dreams—surface manifestations of unconscious memories that man may have instinctually cherished but never intellectually understood.

“In modern times, both physiological and psychological authority has become vested in the medical profession, but the doctor’s familiarity with the biological functions of the organs tends to inhibit him from looking more deeply into their psychological function. However, the simpler minds of old knew, intuited or suspected that the placenta and the umbilical cord had a mysterious value which transcended their physical function. This is clear from the importance attached to the preservation and even the sanctification of placental and umbilical organs.”

Here, Mott not only recognizes ancient man but alludes to the potential superiority of his “simpleness.” From this perspective, Mott would endeavor to create a repository of material rich with novel ideas about the psychological effects of the fetal experience on the individual, building on his psychoanalyst predecessors, but also pulling repeatedly from mythological sources, emphasizing their hidden sophistication.

To summarize in Mott’s words, “the root of all psychological feeling is that primary physical feeling generated or stimulated by the touch of the fetal body upon its uterine surround.” Therefore, aspects of development such as emotional devices of infancy can be seen as efforts to restore its lost connection. The root of sexuality can be seen as the giving and receiving rhythm between the fetus and the placenta. Our gravitational connection to the earth can be felt psychologically as a replacement for our initial connection to the placenta, and so on.

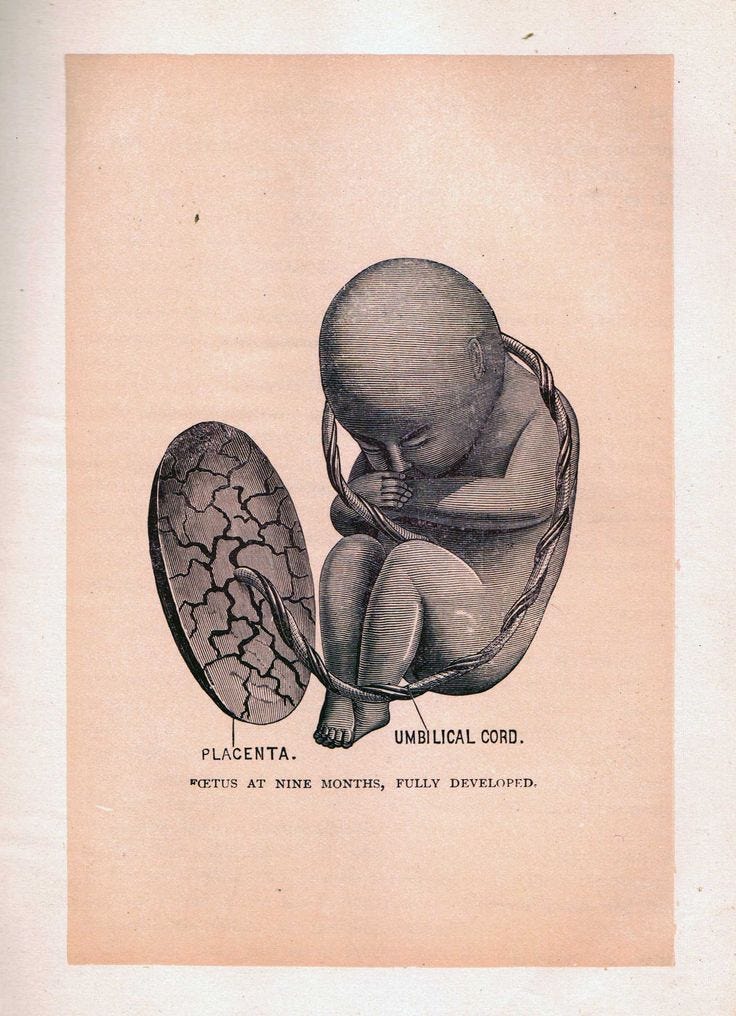

The three primary parts of the womb make up the archetypes that Mott believed occurred widely in myth: the fetus, the placenta, and the umbilical cord that connects them. Mott calls the placenta “an instrument of inheritance [which] transmits a deep organic knowledge stored in the blood.” In mythology, it takes many forms such as the twin, the tree, the cauldron/grail, the foe (poisoner, parasite), and the nurturer/teacher. The umbilical cord, through which blood is transmitted back and forth between the fetus and placenta, often appears as the serpent (especially twined, as the cord is made up of two veins and an artery), the bough, or the dragon. In Western myth, dragons are perceived as greedy, deadly, and malevolent, while in the East they are seen as benevolent guardians—both reflect qualities of the cord. It transmits the building blocks of life from the placenta, removes waste from the fetus, but also becomes less efficient as the fetus grows, eventually becoming the mortal threat that must be slayed to finalize the birthing process.

The central character of the archetypal “hero’s journey” would then be the fetus—defined by Mott as youthful, shining heroes like Apollo, Baldr (‘shining one’), Zeus (‘to shine’), Christ (‘light of the world’), reflected biologically by the sensory intake of the fetus in utero, which comes from small hairs coating the body, all which have nerve endings—the fetus therefore feels in all directions, an image of one who “shines.”

The essence of Mott’s psychology is essentially pagan—predicated on the interconnectedness of all things, where the primary experience of the fetus in utero is not excluded from its later psychological makeup. This idea of “inheritance” also echoes the primordial religious belief in reincarnation. The placenta, a carrier of ancestral information through DNA, serves the sole purpose of defining the “new” lineal incarnation. Its mysterious grandeur remains relevant today in questions of epigenetics, stem cell research, placentophagia, and its unique intricacies as an organ.

Were ancient people ignorant in canonizing the fetal drama as a mythological archetype, or humbly reverent and curious in the face of creation? Today, the medical designation for the placenta is “clinical waste.” Perhaps there is inherent value in overlapping spiritual and scientific thought.

Mott’s interest in the “universal design of creation” centered around the womb as a microcosm guided him towards a unique epistemology synthesizing psychoanalysis, dream and myth interpretation, and obstetric theory. If fetal psychology is an obscure niche, Mott is obscure-squared—both deserve more attention and perhaps will find it in years to come.

Relevance to Neanderthal Paganism

The purpose of this blog is ultimately to demonstrate how the worldview of indigenous Eurasian cultures spawns from their common Stone Age ancestor, the Neanderthal. In doing so, the sophistication of mythology, ritual, and the so-called “primitive” mind that developed them will be argued for.

The defining quality of this worldview is the belief in reincarnation—not based on faith, but genetic reality. Myth and ritual are how rebirth occurs in the mind; they are the vessels in which knowledge was transmitted by our ancestors and, unconsciously, by us. Information is hereby like a specimen preserved in amber, or a dormant gene waiting to be activated. Its power is revealed in our repetition of stories; we feel the instinctual need to continue traditions; we carry out bizarre practices year after year, dragging trees into our homes and leaving money under pillows for fallen baby teeth. All these things point to an unknown history of the mind worth exploring.

For Neanderthals and their various descendants, a subject of particular interest was the unseen: what occurs in the soil, in the body, in stars and cells, that turn the wheel of life? What patterns do they share? There is an emphasis on the microcosm in ancient science—if one understands himself, i.e. the human body, one will understand the universe. This is where the question of creation enters and where fetal psychologists refer to the womb as early man once did.

“The scientific study of the depths of the mind must open the way to a quintessential discipline, one which overflows the boundaries of the camps of religion and science.”

A rich source of information …. well done.

phenomenal! really enjoyed it. also in slavic folk culture there is a ritual for pregnant women to wear a red ribbon near them to protect their children from curses already in utero (not only after being born). just something this piece reminded me of :))