Healer and Deceiver: The Duality of Serpent Symbolism

As we celebrate the Lunar New Year and the Year of the Snake, let's explore how this symbol has endured for thousands of years.

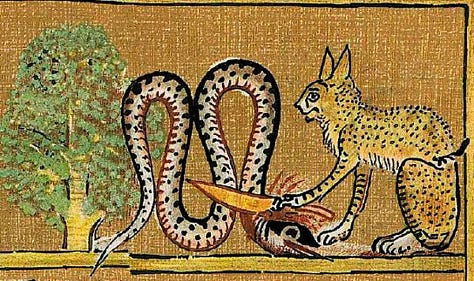

The serpent threads its way through the mythology of nearly every culture, appearing as both a guardian and a threat, a healer and a deceiver. From the earliest records of Egyptian civilization, the Uraeus, a symbol for the goddess Wadjet, the ‘intact one’ and guardian of Lower Egypt, graces the pharaoh's crown as a symbol of royal power. Yet, the chaotic and destructive snake deity Apep was the nemesis of the sun god Ra. In Mesopotamian mythology, the underworld god Ningishzida (in Sumerian, “Lord Productive Tree” or “Good Tree”) was depicted with two serpent heads growing from his shoulders and associated with vegetative growth, but also inspired the deceitful serpent of Eden. In Mesoamerica, the Plumed Serpent deity, known as Quetzalcoatl among the Aztecs and Kukulkan among the Maya, nourished the land through its association with blood and water—but also had a destructive “evil twin” or dark side named Tezcatlipoca.

From the entwined serpents of the caduceus to the petrifying basilisk of medieval lore, the serpent is a fixture of the collective human imagination in its creative and destructive grandeur. What explains its persistent presence? One answer may lie in the Neanderthal, the Paleolithic man of the Northern Hemisphere who first expressed a cyclical worldview through symbolic ritual and art. He is a common ancestor of Eurasian populations, whose indigenous cultures share this worldview and whose many instances of direct symbolic overlap largely remain an anthropological mystery. The prevalence of the serpent as a symbol of death and regeneration may be an inheritance from these archaic ancestors, encoded in the stories that survive to this day.

As we celebrate the Lunar New Year and the Year of the Snake, it is worth considering how this symbol has endured for millennia and what its polarized duality represents.

Serpent as Healer

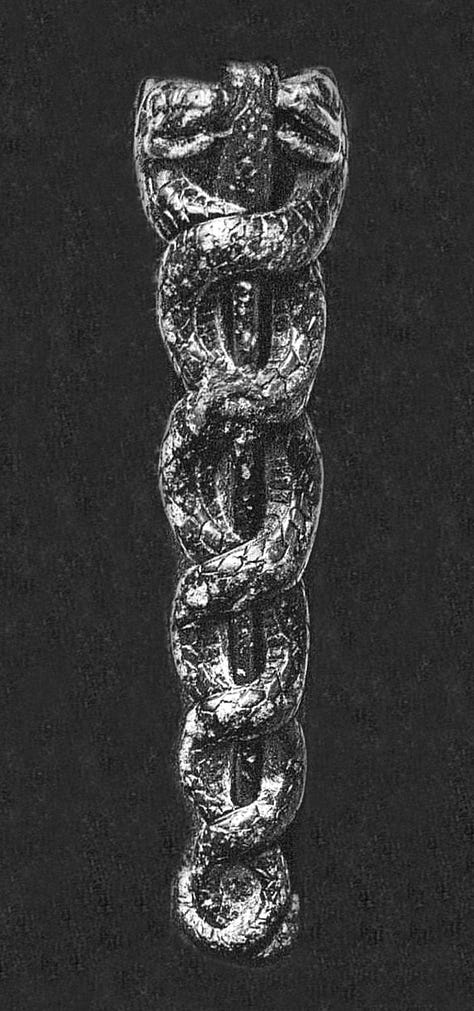

Though often feared, the serpent also appears as a benevolent force in myth and folklore, associated with healing, birth, and regeneration. The Staff of Asclepius, still used as a symbol of medicine today, depicts a single snake coiled around a rod. The caduceus, also still employed in the same capacity, has two entwined snakes coiled around a rod, with wings on top. In Hindu and Buddhist traditions, the Nāgas are powerful serpent deities who guard treasures and sacred knowledge—similar to the perception of the dragon (from Greek drakōn ‘serpent’) in Eastern cultures. Another instance of entwined snakes comes from a tale of creation in Chinese folklore, between the union of Nüwa and Fuxi. The Rainbow Serpent of Australian Aboriginal mythology is also a creator figure, shaping the land and bringing water to the earth. The ouroboros, the self-consuming serpent, signifies eternity and the unbroken cycle of existence.

The Ancient Greeks considered the shedding of skin to make the serpent an obvious symbol of rebirth and healing. In medieval European folklore, serpents were sometimes associated with alchemical transformation, guarding hidden wisdom and elixirs of life. Even in cultures where serpents were seen as dangerous, they were often revered rather than merely feared.

Serpent as Foe

Yet, for all its positive associations, the serpent is just as frequently cast as an antagonist. The tale of Adam and Eve casts the serpent as a deceiver who tempts man into committing the original sin, forever associating the serpent with Satan in the Abrahamic tradition. European figures like the basilisk and Medusa could kill with a single glance. In Norse mythology, Jörmungandr, the World Serpent, coils around the earth and is destined to battle Thor during Ragnarök. The dragon, a close cousin of the serpent, is often depicted as a greedy, malevolent creature—hoarding treasure, abducting maidens, and poisoning the land.

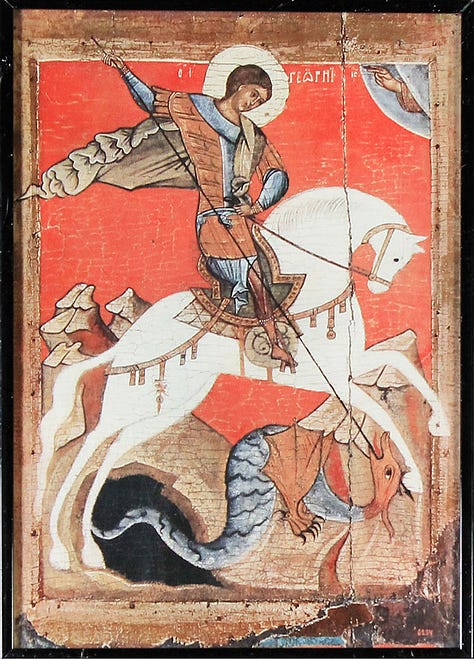

Across cultures, serpents and dragons often appear as foes that must be slain by heroes, from St. George to Siegfried and Fáfnir to Hercules and the Lernaean Hydra, reinforcing the motif of serpents as dangerous, chaotic forces that must be overcome.

The Umbilical Cord

A compelling interpretation of serpent symbolism links it to the umbilical cord—the first connection between mother and child. The cord embodies the qualities of the serpent in myth as the lifeline that sustains and nourishes us, but also as a threat that grows alongside the fetus, eventually culminating in its necessary destruction.

It is directly recorded that the Hopi of North America considered the snake a symbol of the umbilical cord, and hinted at in symbols like the Greek caduceus (the umbilical cord is made up of two entwined veins around an artery much like the caduceus). Countless cultures from Ancient Egypt to remote tribes of Siberia practice birth rituals involving proper treatment of the placenta and cord. Concerning comparative interpretations, Francis J. Mott and Marie Cachet have argued that the mythological serpent represents the umbilical cord, drawing on prenatal symbolism in myth and obstetric biology.

The umbilical cord coils and twists, binding the fetus to its mother. The threat of strangulation looms in utero and increases substantially by the third trimester of every pregnancy. Its biological function is to feed the fetus by transferring nutrients from the placenta while recycling waste from the fetus and providing oxygenated blood in a constant back-and-forth rhythm, a self-consuming loop much like the ouroboros image. As the fetus grows and birth nears, the cord becomes less and less efficient at providing “clean blood” and so becomes a primordial anxiety for the fetus that once relied solely on its consistency—explaining why serpents are so often depicted as both life-giving and deadly, as healers and poisoners.

Other Interpretations

Beyond the umbilical connection, serpents have been subject to countless interpretations in mythology, psychology, and religious thought. The theologian’s view of the serpent as a manifestation of evil, particularly in Christian traditions, clashes with the Jungian perspective, which sees the serpent as a symbol of transformation, an embodiment of the unconscious mind and the instinctual forces that drive human behavior. In The Golden Bough, James Frazer links serpent myths to fertility cults and the agricultural cycle, noting that in many early agrarian societies, serpents were revered as guardians of the land—mediators between the spiritual and earthly realms.

Often, as with other prehistoric symbols, the serpent is anthropologically tied to vague superstitions such as “protection” and “fertility” without a deeper explanation as to the function of the symbol or what it represents. In the umbilical interpretation, ancient man harnessed the ability to explain the biological functions of the cord and its role in creation. Through myth, his knowledge was given a vessel in which to be passed down.

Neanderthal Connection

If the serpent has been with us since the dawn of human consciousness, its persistence may be linked to the worldview of Neanderthals. Evidence from Paleolithic burials and cave sites suggests that they were the progenitors of what became the indigenous spiritual culture of the Northern Hemisphere. The cyclical worldview of “paganism” aligns with the utility of the serpent as a symbol. Just as the ouroboros devours itself to be reborn, and Odin sacrifices himself to himself, the Neanderthals understood life as an eternal cycle, one in which death and renewal are inseparable.

Deep within the caves they once inhabited, where flickering torchlight gave form to their first myths, the serpent may have been a potent, primal image that has remained in our collective memory ever since. Whether as a healer, a foe, or the very cord that binds us to life, the serpent remains one of humanity’s most enduring and enigmatic symbols. As we mark the Year of the Snake, we can recognize in this ancient symbol not just a relic of myth, but a reflection of our origins, stretching back to the first stirrings of human thought.

I think in Western tradition, it is very common to see the snake as a villain, much like the wolf or the fox in other stories. I like the Eastern interpretation of rebirth and fertility. I love your analysis of how snakes represent the umbilical cord, as well as the neverending cycle of life. They are powerful symbols of transformation!

The ouroboros indeed